Historically, electricity pricing has been relatively straightforward: The more you use, the more you pay. But today, that simple equation is not so simple. Increasingly, the time of day when you use electricity factors into the cost as well. It’s called time-of-use pricing, and while it can save money and energy, it’s not always popular.

But before diving into the details of time-of-use pricing, let’s get a key fact out of the way: While we have historically paid a flat rate to use electricity in our homes, the cost to generate that electricity fluctuates constantly. For example, on a hot summer afternoon, when everyone gets home and turns on their air conditioners, power demand surges, and the price of generating electricity with it.

Mark Dyson, a power expert at the Rocky Mountain Institute, says that’s because most utilities deal with those spikes in demand by turning on natural gas power plants.

“Those power plants are just sitting around, waiting to be used on hot summer afternoons,” he says.

LISTEN: “Get Ready for ‘Time-of-Use’ Electricity Pricing”

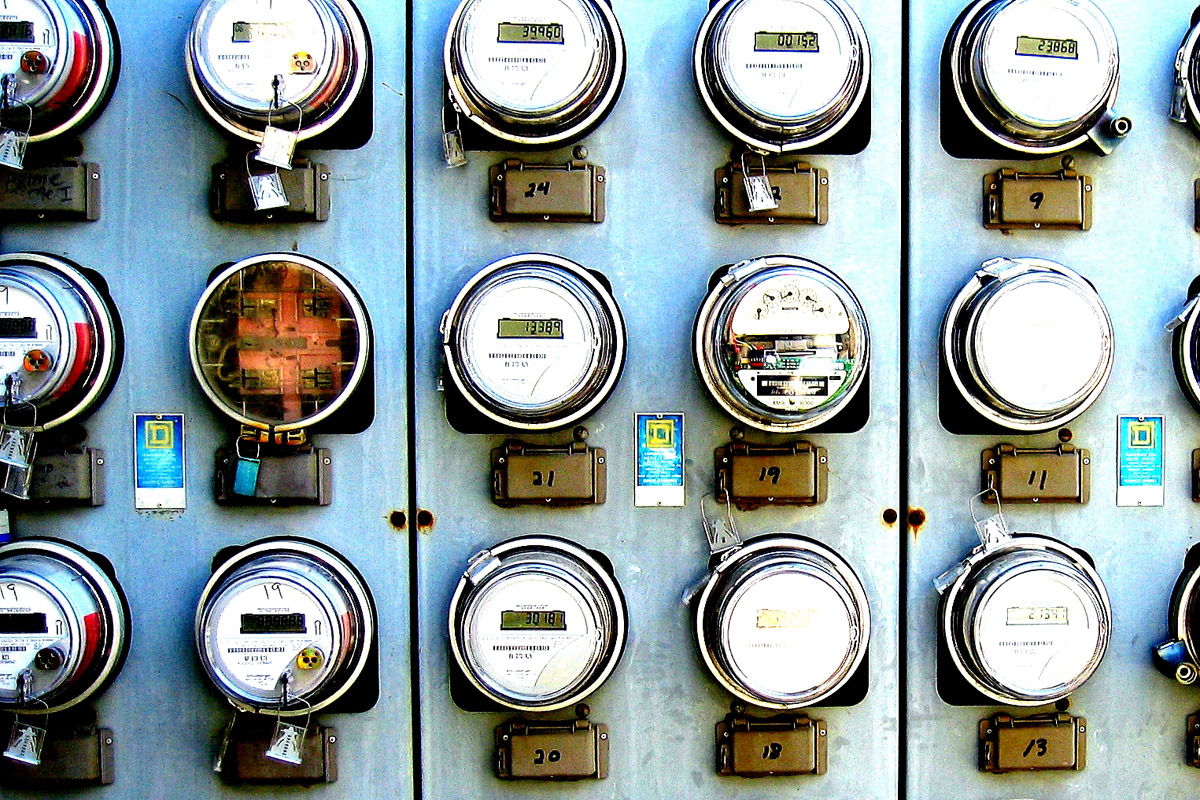

That’s not an exaggeration—a lot of natural gas “peaker” plants only run a few days a year. That obvious inefficiency was hard to get around in the past; there was no way for utilities to convince customers to use less electricity at certain times of the day, because electricity use was metered monthly, not hourly. But today, with smart meters, it’s possible to measure electricity use down to five-minute increments. That enables what utilities call “demand response”—customers shifting their electricity demand away from peak times. One way to do that is time-of-use pricing.

Here’s how Oklahoma Gas and Electric explained it in a 2012 advertisement:

“Energy costs more during peak hours, from 2 [p.m.] to 7 [p.m.] weekdays, when demand is highest. But shift some of your use to the other 19 weekday hours, or all weekend and you can save risk free.”

OG&E was one of the early adopters of time-of-use pricing. For the past few years, the company has had a program called “SmartHours.” As the advertisement says, customers who sign up for the program pay more for electricity on summer afternoons, when it costs the utility more to make it, and less the rest of the time, when it costs less. The price difference ranges from about five cents a kilowatt hour to 43 cents a kilowatt hour.

“Forty-three cents a kilowatt, obviously, is intended to motivate them not to use as much,” says OG&E spokeswoman Kathleen O’Shea. “But, hey, that’s their choice.”

Most people respond the way you would expect: They cut back on their use when the price is highest, usually by cooling their homes in the morning and then turning off their air conditioners in the afternoon.

“The average savings has hovered between $100 and $200 for the four-month period we offer it,” O’Shea says. “But you’ll have people who are saving $500, $600, because some people just really kind of get into this kind of stuff.”

Time-of-use pricing could be the wave of the future. But as of 2014, less than 5 percent of residential electricity customers were enrolled in some kind of dynamic pricing program.

OG&E is also saving a lot of money by not having to build more power plants. That potential savings is one reason utilities from Oregon to Colorado to Texas are starting to offer time-of-use pricing for residential customers. In California, they’re taking it one step further: In 2019, time-of-use pricing will become the default for the state’s three largest utilities.

It’s a big shift from the past. For more than a hundred years, people didn’t have to think about when they used electricity. But Dyson says once people get used to it, time-of-use pricing will benefit everyone.

“It saves money for folks who are able to reduce their consumption during peak hours, and it also saves money for the rest of the customers who don’t have to finance the construction of a new power plant, just to meet peak demand,” he says.

Of course, there are critics too. Some consumers advocates worry that with default time-of-use pricing, customers who aren’t able to change their energy consumption patterns will be stuck with huge bills. There are also those who simply don’t want to have to think about when they use electricity.

But the power sector wouldn’t be the first to employ time-of-use pricing. We pay different prices at different times for parking, airline tickets, hotel rooms, sporting events, car services and movies. Maybe someday, it will seem natural to include electricity in that list.

###

This story comes from our partners at Inside Energy, a reporting project covering energy issues from North Dakota, Colorado and Wyoming.