Khadijah Bey hasn’t had major flooding problems in her Homewood home. But she’s worried.

Bey was hired by Grounded Strategies as a “stormwater ambassador” in November to learn about and educate people in her neighborhood about flooding issues. That means she has been going door-to-door in Homewood, talking with neighbors about what they see.

“A lot of residents are having flooding in their basements. A lot of residents,” she said. “It just makes me wonder why so many other people are having it?”

Her best guess: the rain is getting more intense. “It just doesn’t rain,” she said. “It seems like it storms nowadays. It just storms.”

New plan to prepare for flooding

She’s right, according to the city of Pittsburgh’s new stormwater plan for new buildings and infrastructure published in March. The average amount of rainfall per year has crept up since 1840, from about 30 inches per year to an average of around 40 inches per year today.

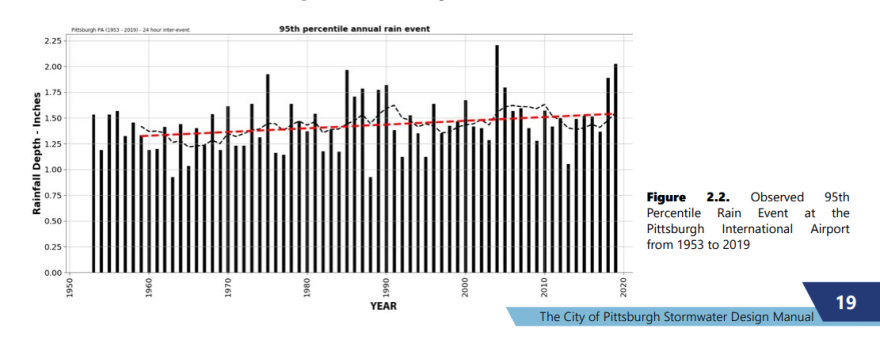

And the very worst storms have been getting even worse. In the last 60 years, the wettest storms have become about 13% wetter on average, according to the city. The wettest storms are defined as the top 5% of storms with the most rainfall. Climate scientists expect these storms only to get more intense as more heat increases the amount of moisture in the air.

Khadijah Bey takes notes during a flooding workshop at the Carnegie Library in Homewood put on by the Army Corps of Engineers on May 25, 2022. Photo: Oliver Morrison/ 90.5 WESA

And it’s these storms that are of utmost concern to local water engineers, such as Tom Batroney. Many of the roads, bridges, tunnels, pipes and buildings that are built are designed to handle water from the heaviest rainfalls. But when the rain is 13% heavier, he said, roads and buildings flood. And even more rainfall is projected for the future.

If you install a new piece of infrastructure, he said, “You have to be able to make sure it’s going to work not only today but tomorrow.”

So the city now says we should expect the worst storms to produce about 1.66 inches of rain. That’s a lot of water. It’s about 45,000 gallons of rainfall per acre. That’s about 5,000 gallons per acre more than what we see now. But if the trend over the last 60 years continues, Batroney said, these storms will get worse.

“You are never going to be 100% correct about the future,” Batroney said. “But you take the best information that you have at your disposal as an engineer and try to make a decision about what that future may be.”

Protecting homes and businesses

But it’s not just city money at stake. Residents are hurt when their homes get flooded.

“For every $1 you spend on [flood] mitigation, how much do you think it saves you?” asked Andrea Carson, a community planner for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers at an educational workshop at the Carnegie Library in Homewood on Wednesday. After one person guessed $4, Carson said the correct answer: $6.

The Army Corps of Engineers has been putting on a series of workshops to educate residents about flooding and how they can protect themselves. On Wednesday, Carson talked with a handful of residents in-person and on Zoom about how to prepare their homes.

Many of the efforts she recommended are simple: Raise your electricity sources and appliances in your basement, so when it floods, they won’t be damaged. Take sentimental items off the floor of the basement. Move boilers out of the basement. In the Chartiers Creek area, Carson said, some businesses have raised their first floors by a foot or two.

Carson also told residents to remove trash and debris from storm drains. “What happens if that storm drain is dirty?” she said. “Well, it’s not going to go into the storm system as it’s intended but instead is going to back up and come back onto your property.”

One of the pieces of advice Bey said she learned at the flooding workshop was to go outside when it’s raining and walk around her whole property. The idea is that then she can better see where the water is moving and how it might be getting into her home. It’s a piece of advice she said she’s going to pass on to her neighbors as she continues to talk to them about flooding. Bey, like many of her neighbors, she said, has two vacant lots nearby she takes care of. And many also have abandoned homes that cause problems.

“They’re either abandoned or people left them and the gutters are gone and the rain is just coming down,” she said. “And that presents a problem for the person who still lives there.”

Flooding dangers

Flooding isn’t just an issue of dollars and cents, Batroney said, it’s a health hazard, especially in June and July, the months with the highest average rainfall in Pittsburgh.

Batroney said he and his wife were in Dormont in June of 2018 when he saw black clouds in the distance. Even before it started raining, he said, “Amber, we have got to get out of here. I mean, we just cannot be anywhere in this valley.”

To get home, they would have to drive down Route 51, a road that winds alongside the Saw Mill Run stream.

“You don’t want to be anywhere near these main little valleys that are in Pittsburgh when it’s June and July and there’s threat of a serious rainstorm,” he said. “You want to run. As the name in the title of the stream [implies].”

Batroney’s intuition proved correct. Security camera footage from a home in Bethel Park later that day showed how fast the flooding can occur. By 8:23 p.m., the water had just started creeping up the driveway. And within five minutes, the water had reached the house. And two minutes later the front yards all along the street had turned into a stream so high that it almost entirely submerged the back wheel of the pickup truck parked in the driveway.

Even though a foot of floodwater may not seem that dangerous, according to flooding resources from the Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority, it’s enough to carry away an entire car. And only six inches can sweep away a person. One person died in that June 2018 flood when they tried to walk through the flood waters.

Despite these increasing risks, the flood workshop in Homewood on Wednesday had only a few attendees. In 2018 and 2019, Pittsburgh saw two of the three wettest years in history. But the last two years it rained about 40 inches — that’s a lot more than 180 years ago — but it’s about average these days. Although the amount of rain is trending up, from year to year, it can still vary widely. And it’s impossible to know exactly how much rain will come before it happens.

Although the city’s current stormwater code requires developers to prepare for an increasingly wet future, that wasn’t always the case. One of the reasons there is so much flooding in Pittsburgh now, Batroney said, is when the current infrastructure was built 50 or 100 years ago, engineers didn’t accurately project how much water we’d be getting now.

“Every bridge crossing and every road that goes over a stream, there’s likely a pipe there that potentially could be flooded,” he said.