Many rust belt cities, including Pittsburgh, are “shrinking.” Some have lost so many people that highways are unneeded, and cities are finding new uses for them.

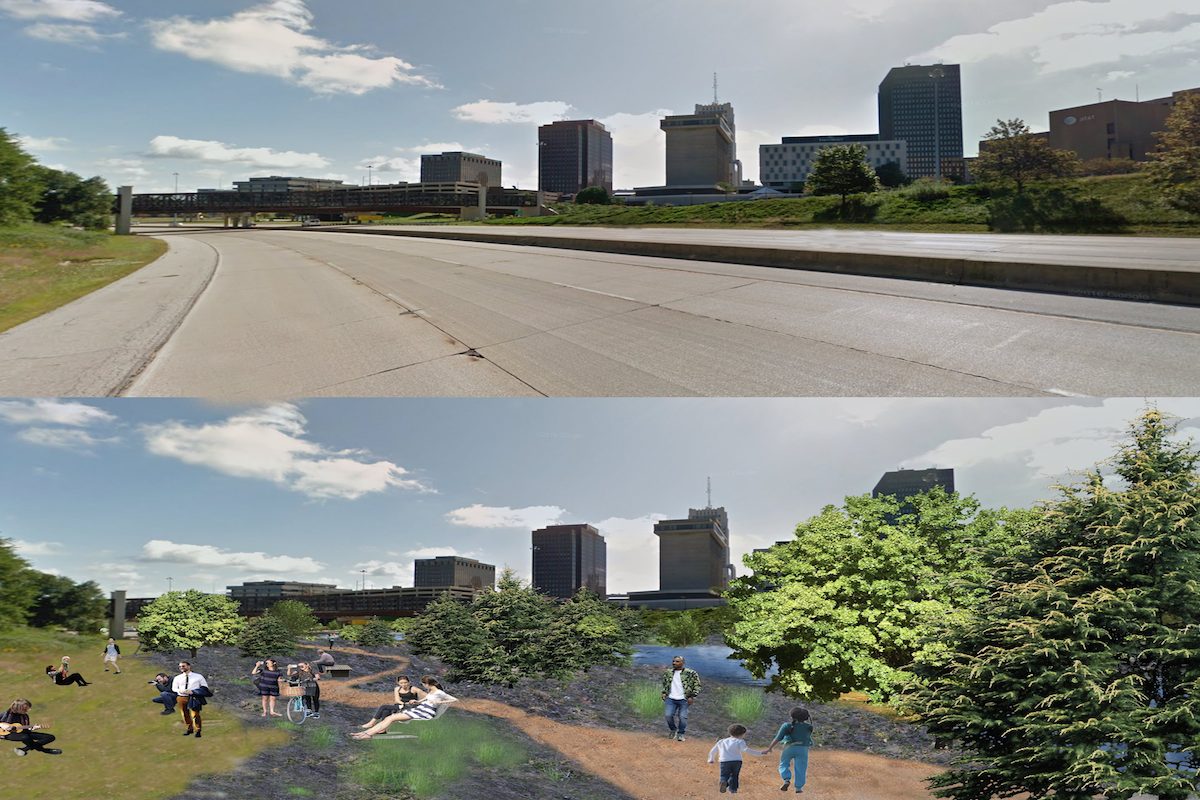

In Akron, Ohio, traffic from State Route 59, known as the Innerbelt, has been rerouted to side streets, and the highway itself is empty. It’s been shut down.

The highway’s construction in the 1970s created a barrier between the largely African-American neighborhoods of West Akron and the city center. It created social and economic rifts that still affect the city.

Kyle Kutuchief, Akron program director for the Knight Foundation, says that the development of those neighborhoods took a big hit because the highway cut them off from downtown.

“It’s been this Great Wall of China that’s pinned in downtown for forty years,” he says.

LISTEN: “One City is Transforming a Highway into a “Pop-Up Forest”

Now the Knight Foundation is working with Akron on a new vision to make the highway a place for people instead of just cars. It’s part of the Knight City’s Challenge to invest in communities to help them become more successful. Shutting down the Innerbelt will open up more than thirty acres of prime real estate to try something new. And the Foundation’s reimagining of the space is being led by San Francisco-based artist, Hunter Franks.

In 2015, when the highway was still open to traffic, Franks got the state to close Route 59 down for a few hours. He set up a really long table right on the highway and hosted a community meal for 500 Akron residents from all 22 of the city’s neighborhoods. While they ate, people talked and wrote down what they might like to see next on the site. Most wanted more public space, and more green space.

“I think the juxtaposition of this freeway and all this concrete with something that is so soft and welcoming and gentle to people in a park, or whatever the green space may end up looking like, that was really something that people connected with,” says Franks.

Now, Franks is using a grant from the Knight Foundation to create something of a “pop-up forest.” For a few months starting next spring, they’ll bring in temporary trees and plants, add seating, and offer programming—things like concerts, a farmer’s market, and movie screenings.

Repurposing old infrastructure isn’t unique to Akron. “This is a phenomenon that’s definitely happening across the country, and internationally as well,” says Joshua Newell, assistant professor at the School for Environment and Sustainability at the University of Michigan.

He says the High Line in New York City is the poster child for this kind of infrastructure redevelopment. It used to be an above ground rail line, and it was converted into an elevated park and walkway through lower Manhattan. “And now it’s a major tourist attraction in Manhattan, and brings people from all over the world to walk along the Highline,” says Newell.

But critics say that property values and rents near the Highline have skyrocketed, pushing out local businesses and lower income residents.

“There’s a very real danger of increasing property values around these very attractive, green spaces in the city. And so that has to be a continual effort by city officials and community to guard against,” Newell says.

And it’s just having that rhythm of life and activity and interest in the city.

In Akron’s quiet downtown, where few are walking around on a hot summer day, the Knight Foundation’s Kyle Kutuchief says gentrification is less of a concern. Many people work in the city’s high rises, but he wants to see them on the streets.

“That people don’t just sit in their cubicles and have Jimmy John’s delivered and get back in their cars and go home. That there’s, you know, ‘Let’s go meet for breakfast. Let’s go walk to the food trucks and grab lunch,’” he says. “It’s just having that rhythm of life and activity and interest in the city.”

Kutuchief hopes the pop-up forest will bring people together, and spark some creativity for what’s next in Akron. It could also help fuel similar projects in cities around the country.