This interview was first published on April 21, 2021

Williamsport, Pa. in Lycoming County was once a logging boomtown in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, until the forests were depleted and the industry went bust. Little League baseball was invented there before World War II, and the county seat is now the home of the Little League Baseball World Series.

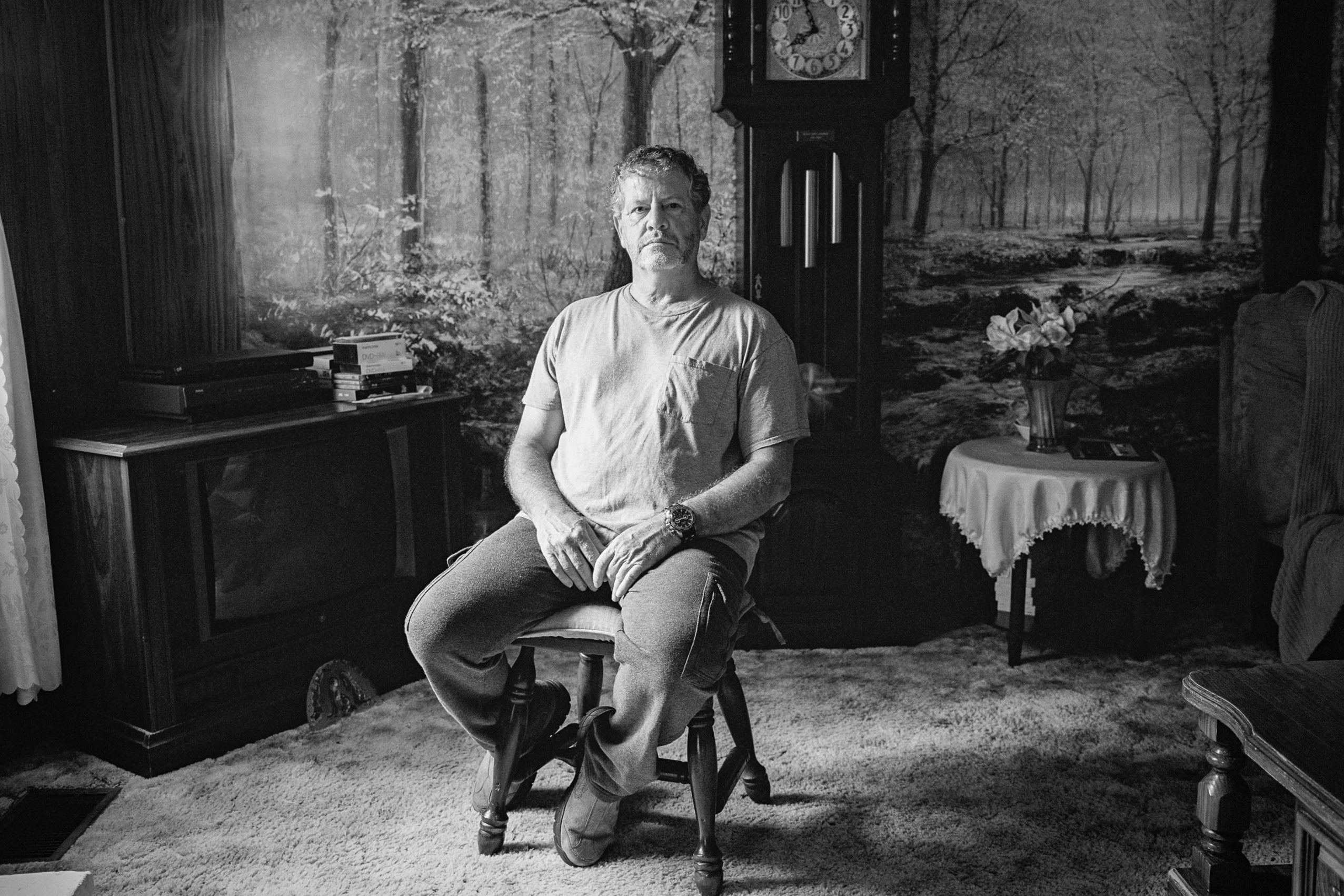

Colin Jerolmack. Image courtesy of Princeton University Press.

But the biggest thing to come to the region recently is the natural gas industry. Landmen looking for residents to sign gas leases, and later gas industry workers revitalized the retail economy, providing a demand for new hotels, bars, and restaurants, and renovated housing.

But fracking also caused upheaval over the disruption and environmental degradation in the rural communities surrounding Williamsport, and challenged the rural values of independence and sovereignty over private property.

Colin Jerolmack, a professor of sociology and environmental studies at New York University, came to Lycoming County over the course of the fracking boom to meet landowners and others impacted by the industry.

He even moved to the area for eight months for research. The result is the newly released book Up to Heaven and Down to Hell: Fracking, Freedom, and Community in an American Town. The Allegheny Front’s Karea Holsopple spoke with Jerolmack about some of the themes in the book.

LISTEN to their conversation

Kara Holsopple: In the book, I think you’re saying that fracking is unique in that it’s a private decision that a landowner makes to lease land and it’s between the company and the landowner. But that doesn’t take into account the impact on the community or to the planet. You call that the “public/private paradox.” How did that manifest when it came to fracking in Lycoming County?

Kara Holsopple: In the book, I think you’re saying that fracking is unique in that it’s a private decision that a landowner makes to lease land and it’s between the company and the landowner. But that doesn’t take into account the impact on the community or to the planet. You call that the “public/private paradox.” How did that manifest when it came to fracking in Lycoming County?

Colin Jerolmack: Pennsylvania is one of many oil and gas drilling states where more or less municipalities are not allowed to control or regulate fracking at the local level. What that means is that fracking, in my view, is actually less regulated than many other land uses at the local level, especially in a place like Pennsylvania.

If you’re a restaurant owner and you want a liquor license, you have to go through this whole process where people can come in and say, “We don’t need another liquor license. There will be too many people drunk driving on the road.”

But fracking basically, while there are still, of course, public permit hearings, these are rubber stamps. This industrial use is allowed in every zone, even agricultural, even rural, where other industrial uses would not be allowed.

The center point of the book is this interesting thing where private property rights are so sacrosanct — that I ought to be able to do what I want on my property, as if that’s akin to free speech. But the idea of free speech is that my use of free speech does not inhibit you from using free speech. That’s where this idea of what I call the public/private paradox comes into play, because the whole normal way that we think about individual liberty and private rights are you are allowed to exercise them because they are viewed as separate from the public sphere.

The center point of the book is this interesting thing where private property rights are so sacrosanct, that I ought to be able to do what I want on my property, as if that’s akin to free speech.

You can love who you want to love because if I marry somebody who’s of the same sex as me, that doesn’t inhibit somebody else from marrying somebody in the opposite sex is them. But leasing your land and otherwise using private property rights in ways that can create the spillover effects, does have public impact and is in the public interest to be regulated. But it’s legally framed as private.

So on the ground in Lycoming County, like in so many other places in Pennsylvania, I followed families [for whom] that impact was explosive levels of methane in their water from their neighbor’s gas well being drilled, the roads being torn up, people being unable to sleep and have their windows closed and their blinds drawn, even on a summer day when they’d like to have them wide open, because of the noise.

Holsopple: You point to an irony in the book which is that signing leases with the gas industry did impact the sovereignty of people over their land. Landowners who signed a lease found there were guards posted on their property. They couldn’t go up and down their driveway. They didn’t have a lot to say about where well pads were placed, so they kind of lost what they prized most, which was control over the property.

Jerolmack: That’s right. One main character who I used to tell that story, although there’s others as well, is George Hagemeyer, who owns 77 acres. He leased and he was very supportive of drilling. He would be down there on the pad talking to the workers every day and would even say that people ought to make him a spokesperson for Anadarko Energy Company, who was the one who held the lease because he just thought it was so exciting, not only making the money but that he would be producing energy for America.

He actually made decent money, and he did not wind up with any contamination. His first royalty check for just a couple months of production was $34,000. In the end, when he came to my class to give a lecture, he told them he wished he hadn’t drilled. It was really sort of puzzling at first because he wasn’t one of these folks that had the worst happen to him.

Separators on the well pad in George Hagemeyer’s backyard. Image by Tristan Spinski for Colin Jerolmack

But what happened was, he didn’t realize how much of his own land sovereignty he had signed over. When they lease your property, it can be decades. It’s a five-year lease, unless they drill. If they drill, it’s in perpetuity, as long as they are producing.

They had said to him, ‘Don’t go on the well pad.’ But he didn’t really think that they meant much of it. They had installed a security camera that he didn’t even know about, and he got a call when he walked on his well pad that he was going to be arrested.

He didn’t know that they were going to be withdrawing millions of gallons of water from a creek until he saw it published in the classified ads of the local newspaper. So in all of these ways he just didn’t really understand that when they leased this land, it’s their land in many ways.

Holsopple: You write that George is not an environmentalist, and he doesn’t have a favorable opinion of anti-fracking activists. You say in the book anti-fracking activists should perform a postmortem on their efforts because they failed in large part to engage local residents in Lycoming County. How do you see that divide, and what could they have done differently?

Jerolmack: So, first, I’ll talk about the divide in broader terms, because I think I didn’t know it at the time, but what I found, this sort of disconnect between so-called activists and the local community, is pretty consistently shown across states. There’s a national debate about fracking. It’s a highly polarized issue, although in any locale it’s usually not polarized.

Cities and coasts are mostly against it, and then the people who live in the rural heartland where most drilling is occurring are for the most part for it. Of course, there’s some variation.

If you get more specific, the closer somebody lives to a natural gas well or oil well, the more likely they are to support it. How this played out here is that there was a local anti-drilling group called the Responsible Drilling Alliance, which was quite small. It’s still there — only about a dozen sort of core members and then a more expanded listserv.

Their idea of being against fracking was being a liberal, urban interloper who would come in…and wasn’t a part of the community and whose answer was always more regulation.”

Often even they and what they were doing got lost amidst the much more vocal and occasional presence of activists from New York City, from Philadelphia, from Pittsburgh, who sometimes would literally come in on busses. And most infamously, even though it was in a neighboring county, everybody I talked to would talk about when Yoko Ono and Sean Lennon and Susan Sarandon took this tour through Susquehanna County, and basically, this struck a lot of locals as off-key.

Fracking behind a cemetery in the hamlet of Cogan House. Image by Tristan Spinski for Colin Jerolmack

What is really fascinating about this is, to go back again to the Responsible Drilling Alliance, which was the local group and was mostly quieter, a lot of the specific things they were pushing for, like the ability of municipalities to control fracking through zoning, not allowing impoundment ponds, wanting to force companies to use water pipelines rather than driving all those trucks on the road — those were things that a lot of landowners supported and they could have gotten behind.

But their idea of being against fracking was being a sort of liberal, urban interloper who would come in and raise a stink and wasn’t a part of the community and whose answer was always more regulation. That’s the real disconnect.

If the way that environmentalism gets framed is to ban fracking and greater regulation over private land use, those kinds of things are going to turn locals off.

What I think they could have done differently — and there were some people doing this, like Ralph Kisberg, who’s a co-founder of Responsible Drilling Alliance — I think you need to try to take the politics out of it entirely.

So, for instance, one of the things that Ralph and a couple other people would do, but not many others did, was if something went wrong with a community member, they would just show up and say, how can I help you research the problem? Do Freedom of Information Act requests to find out as much as possible about the source of contamination. Offer them pro bono legal help. When Ralph did this, he found that people were responsive.

I mean, I do want to be careful. I don’t mean to say that, everybody should just bend over backwards to cater to rural, white, working-class people. But a lot of folks who own land out there are fifth-, sixth-generation landowners, and they see themselves as land stewards.

It’s not that they’re opposed to any kind of protection on the land. I just think that if the way that environmentalism gets framed is to ban fracking and greater regulation over private land use, that those kinds of things are going to turn locals off.

So if there’s a way that people who are involved in environmental protection around fracking and other issues to tailor the particular environmental policies that they want to focus on to local communities, and to disassociate [those policies] from a larger agenda of say, greater government regulation overall, I think that we can bridge this divide a little bit.

Holsopple: There’s also the issue of fracking on public land, like state forest land. You write about the fight to preserve Loyalsock’s State Forest’s Rock Run from fracking, where there are pristine waterfalls and swimming holes. How was this different from what happened on private land?

Jerolmack: A lot of locals supported it. Actually, once it was discovered that this portion of the Loyalsock, colloquially called Rock Run because of the stream, was going to be drilled on, the Responsible Drilling Alliance actually had a pretty easy time getting hundreds of people to turn out at public hearings and events. Well over 12,000 people signed a petition, which for a small rural county is quite a lot.

Hearings in which state representatives from all over the state came garnered statewide media attention. It was actually the only campaign that the Responsible Drilling Alliance, I would argue, was successful in mobilizing rural, conservative landowners. This is what showed me that people do have an understanding, even if they’re quite individualist, of the public good.

I think a lot of people understood that this was a beautiful, relatively pristine area that’s surprisingly close to settled areas. Even people who lived in more suburban homes could in 10 or 15 minutes, be out here and be swimming in a creek so pure you can drink out of it. People had a sense that this public good was at risk.

Holsopple: What have we learned from fracking that we can apply to other environmental concerns?

Jerolmack: This is why I use this concept of the public/private paradox where, again, just to reiterate this idea that we see leasing as a private decision, but it actually should not be construed purely as a private decision because it impacts the public both immediately, of course, your neighbors, but also the planet.

So to me, the public/private paradox is a more transportable concept. You know, many of the decisions that you and I and other people make on a day to day basis, what kind of car I drive, how far I commute, how much I consume, how much I throw away, all those things are basically viewed as purely private decisions in which we are not at all regulated or very lightly regulated.

But all of those decisions impact people in the same way that leasing impacts neighbors. It’s just usually harder for us to see because it might be the plastic in the ocean or rising seas that are inundating people in another country who have to relocate. Or it might be future generations which don’t even exist yet.

I’m not a policy expert myself so I don’t have a list of all the prescriptions of what to do with this, but I do think that this helps me understand why the United States so disproportionately consumes world resources and disproportionately contributes to waste.

We often frame it as sovereignty and rights. But I guess that we don’t frame it as how the externalities, the spillovers, infringe on other people’s rights and sovereignty. That’s the way I’m trying to shift the conversation.

If we view profligate energy use and waste production as something that ought not be a private decision, and if we explicitly link that to violating or infringing on other people’s rights, other people’s rights to enjoy environmental goods, other people’s rights to continue to live in their home under sea level rise, then I think that maybe that can change the conversation a little bit.

Colin Jerolmack is a professor of sociology and environmental studies at New York University, and author of the newly published book Up to Heaven and Down to Hell: Fracking, Freedom, and Community in an American Town, published by Princeton University Press.