By Laura Harbert Allen | Ideastream Public Media

On a Sunday morning in late August, about 30 people were scattered in the wooden pews of the sanctuary for worship at Centenary United Methodist Church in East Palestine. It was the weekend before school started, and church member and lay leader Bill Sutherin said that some church members were out of town for one final summer break.

“Normally, we have about 40 people in church,” he said.

But Sutherin also acknowledged that’s a lot less than it was back in the church’s heyday era of the 1950s and ‘60s when “we had almost 300 people in church on Sunday, and over 1,000 members.”

Centenary reflects a well-documented national trend of shrinking church attendance in the U.S. A 2021 Gallup poll showed that fewer than half of Americans are members of a church, a first since that organization began tracking church participation data in 1937. And since 2017, about 1 in 5 Americans have said they don’t identify with a particular religion.

But these statistics don’t tell the whole story. A recent study of United Methodist Congregations in North Carolina showed that rural churches generate $944 million for that state’s economy.

“We represent our faith and that means we represent Jesus and God. We’re there for them if they need us.”

Bill Sutherin

Rural churches, said Bob Jaeger, president of Partners for Sacred Places, which conducted the study in partnership with the Urban Institute at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, “are not just worship places, but civic assets.” Churches provide food, childcare, and other public-facing services that reach beyond names on church attendance rolls.

That statement rings true in East Palestine, where churches sprang into action after a Feb. 3, 2023, Norfolk Southern train derailment left residents scrambling to trust the safety of the town’s water and air. Pallets of bottled water were distributed from the parking lots of First United Presbyterian Church and the Church of Christ, just blocks away from Centenary.

In the months since the derailment and controlled burn, local churches have distributed hundreds of air purifiers to residents, some of whom remain unsure of whether the water and air in town are safe. Churches have also hosted town hall meetings that include Environmental Protection Agency officials, grassroots organizers, and Norfolk Southern representatives.

And, in March, Centenary became Norfolk Southern’s headquarters for clean-up operations in East Palestine. The company signed a one-year lease with the church soon after the derailment, and about 150 Norfolk Southern employees and subcontractors are in and out of the building regularly, which sits in the middle of the town’s primary business district.

- National Academies gather East Palestine health questions to consider future research

- Eight months after the East Palestine derailment, some residents wonder if they’ll ever go home

‘The hub of East Palestine’

“We needed a place to call headquarters,” said Jeremy Vranesevich, who works as Norfolk Southern’s community liaison in East Palestine. “And it’s not like this is Cleveland or Pittsburgh, where there’s plenty of office space.”

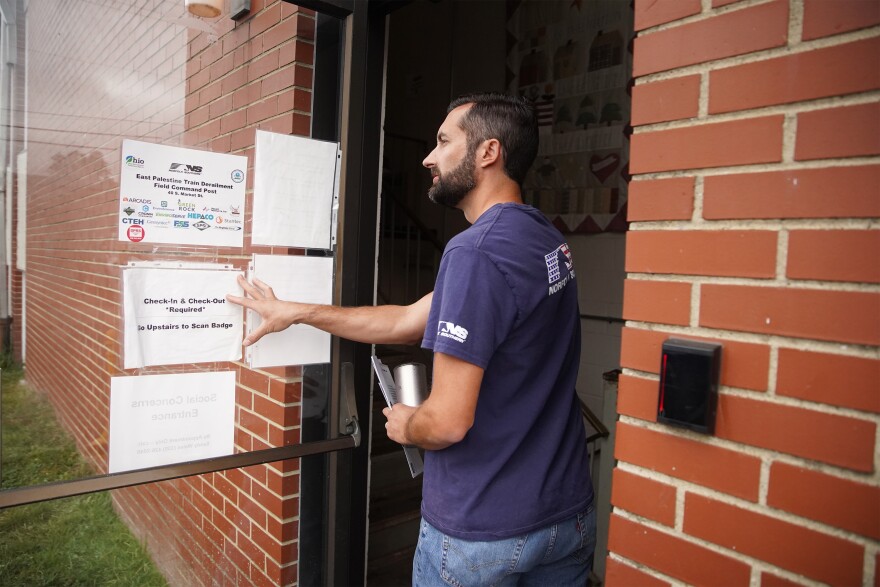

Jeremy Vranesevich, Norfolk Southern’s community liaison, works from the Centenary United Methodist Church on Monday, September 25, 2023. Photo: Ryan Loew / Ideastream Public Media

Vranesevich was a machinist for Norfolk Southern living in East Palestine when the derailment occurred in February and became the company’s community liaison in March. For him, Centenary’s size and location in the middle of town are ideal.

“Everyone in town knows where the church is,” he said, adding that “we’re also close to local businesses. We can walk out the door and visit with them in minutes.”

Of course, there are trade-offs. Centenary still has access to the church sanctuary for Sunday worship, but the newer Sunday school wing – including nine classrooms, a choir rehearsal space and a fellowship hall – is reserved for Norfolk Southern’s offices. Security guards are on site, directing worship attendees on Sunday morning to the front entrance of the church, away from the company’s designated office space.

And during the week, the parking lot is “always full,” said Vranesevich, adding that “it’s a lot of traffic for a small town.”

The congestion meant that the church could no longer offer its monthly $10 pickup lasagna dinner to the community.

“The amount of traffic,” Vranesevich said, “just made it impossible.”

Instead church members now cook lasagna for Norfolk Southern employees who are on assignment in East Palestine. The dinner, said Vranesevich, is something employees look forward to.

“These folks are away from home for weeks at a time,” he said. “A home-cooked meal is a nice break.”

Jeremy Vranesevich at the Centenary United Methodist Church. Norfolk Southern signed a one year lease with the church soon after the derailment, and about 150 of its employees and subcontractors are in and out of the building regularly. Photo: Ryan Loew / Ideastream Public Media

“They tell me the church is a home away from home,” said church member Bill Sutherin. “Several of them have told me that sometimes they go into the sanctuary just to sit in a quiet place.”

Sutherin is also quick to point out that, despite a large local footprint, Norfolk Southern has cooperated with the church.

“There’s never been a problem for us accessing the church for meetings or things like weddings or funerals,” he said.

Churches and disaster response

The wide-ranging response – from handing out bottled water, air purifiers and distributing food to providing facilities for Norfolk Southern’s ongoing cleanup work in East Palestine – shows just how embedded local churches are in disaster response efforts.

“There’s this kind of internal network that’s very community-based, very locally grounded,” said Jamie Shinn, an assistant professor of geography at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF) in Syracuse, New York. Shinn conducted extensive research in rural communities in West Virginia after heavy flooding in 2016 temporarily displaced 2,000 residents in that state.

“I was not prepared for just how important churches and faith-based organizations were in disaster response and care,” she said.

Shinn describes two levels of church work. Local churches like Centenary, who are already a trusted presence in local communities, are often a point of first contact for residents after a disaster.

Then, there are nationally known faith-based groups – like the Southern Baptist Convention’s Disaster Relief organization, the third largest in the country, behind the American Red Cross and the Salvation Army – that also provide assistance during recovery efforts. Yet another organization, Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster (VOAD) has chapters in every state and several U.S. territories. VOAD coordinates the efforts of volunteer faith-based response teams with government agencies such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

These volunteer faith-based organizations do a lot – from building homes and bridges, to distributing resources such as food, water – and in East Palestine – air purifiers.

And government entities, like the Environmental Protection Agency, for example, count on VOAD and other faith-based organizations as a vital component of disaster response.

“They are part of the infrastructure in some ways,” said Shinn.

A train passes through East Palestine on Monday, Sept. 25, 2023. Photo: Ryan Loew / Ideastream Public Media

But one question, Shinn asks, is whether faith-based organizations are bridging a gap that public and civic infrastructure should be filling. Another is whether church outreach efforts post-disaster effectively reach non-church members. Anecdotally, the answer could be seen in the line of people, Shinn recalled, outside a food pantry in a local Presbyterian Church in Greenbrier County, West Virginia, after the 2016 flood.

“Far more people were in that line than ever attend that church on a Sunday,“ she said, adding that the way churches bring people together “is an embodiment of the type of social capital that does exist in these places.” That’s important, Shinn said, because “we can’t just think about rural communities as vulnerable. These deep local connections make them resilient.”

East Palestine resident Donna Welsh is a case in point.

“I don’t go to church,” she said, “but I have picked up lasagna at the big church downtown,” referencing Centenary’s community lasagna dinner.

In the weeks after the derailment, Welsh picked up bottled water at the Church of Christ and an air purifier from First United Presbyterian Church, which also houses The Way Station, a thrift store and resource center that has expanded its services to meet community needs since the derailment.

Kelly Mattern stocks baby formula at The Way Station, a thrift store and resource center inside the First United Presbyterian Church in East Palestine. Photo: Ryan Loew / Ideastream Public Media

The Way Station now occupies 80 percent of the First Presbyterian Church and hosted a grand re-opening in August.

Welsh was there.

“I like looking around the thrift store,” she said, adding that she “almost always finds something.”

The church and community remain

For Bill Sutherin, East Palestine and Centenary United Methodist Church are home. He also represents the East Ohio Conference of the United Methodist Church for the Ohio chapter of VOAD and has watched as numerous faith-based organizations have worked to help East Palestine residents recover.

But there is still work to be done.

“I think we have about 200 residents who still haven’t moved back to town,” he said. “Things aren’t back to normal just yet.”

The local church, he adds, is a point of connection for the community as it continues to recover. That’s important, he said, because even in small towns like East Palestine, people don’t know their neighbors like they used to.

He also acknowledges the role faith plays in Centenary’s ongoing efforts to serve their town.

“We represent our faith, and that means we represent Jesus and God,” he said.

“We’re there for them if they need us.”